“A watch that ticks is wrapped around my wrist.”

—Jeff Tweedy

At some point in the late 2000s, early in my tenure as an Assistant Professor and inspired by my colleague Robert, I started a subscription to the New York Review of Books. Robert and I built most of our conversations around this magazine. As we both routinely taught evening classes at the time, I have fond memories of our discussions amid the East Texas darkness. I remember two specific conversations to this day: one about Bruce Chatwin, who had shown up in some sort of context, and one about an essay by Zadie Smith. This piece, “Killing Orson Welles at Midnight,” centered on a film by Christian Marclay called The Clock. This twenty-four-hour art piece fuses clips of clocks (and other references to time) from hundreds of films into a monument to the infinite patterns of our days. Or, as Smith writes, “The Clock is a twenty-four-hour movie that tells the time.”[1]

Clearly there are two types of time, real and staged. There are a few ways to say that. Accidental clocks versus deliberate clocks. Time that has been caught on film versus time that has been manipulated for film.

I have thought about this essay over the years more than I would like to admit. Partly because I knew I would never see the film, partly because it seemed like such an audacious experiment, and partly because I could not quite comprehend the monumental task of finding the references and bringing them together in chrono-coherence. This final part is amusing on the surface since the clips should just be tacked to the clock, and there is your narrative. But something else seemed to be happening with this film. At any rate, the essay wormed its way into my brain. In November 2023, I had the chance to ask Zadie about this essay after one of her readings for The Fraud. When I told her I could not quite shake one of her essays from a dozen years earlier, she responded, “Uh oh.” But she lit up when I mentioned The Clock, and she talked about its continued resonance in part precisely because of its lack of, maybe its impossibility, of being screened again.

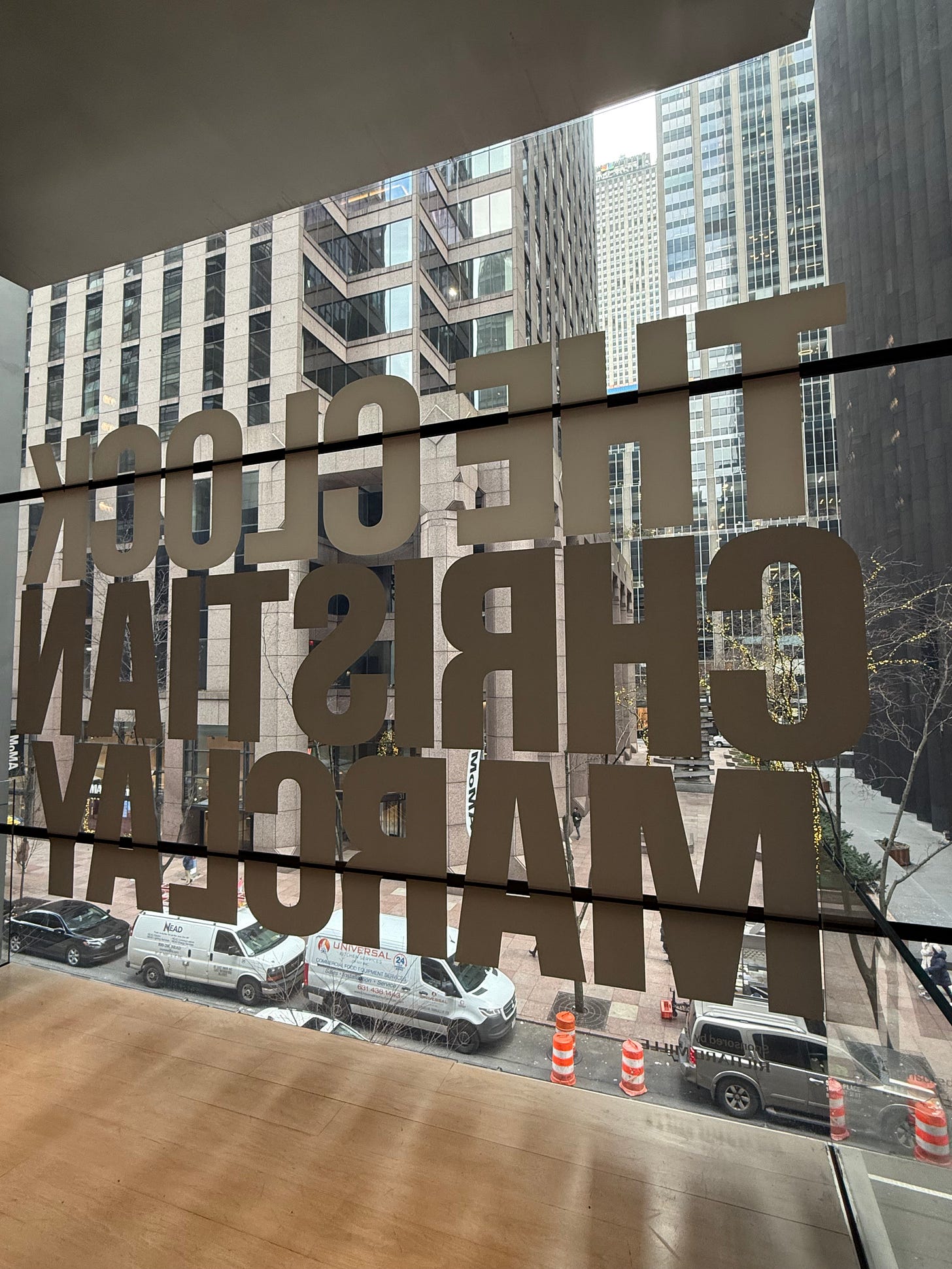

Then, this past November, the Museum of Modern Art brought The Clock back to life with an exhibition of the film (which runs until February)—including a handful of twenty-four-hour screenings. And this last week, as I was in New York City, I was finally able to experience at least sections of the piece—a screening almost 13 years in the making. The Clock was both exactly what I had anticipated and even more interesting in terms of craft. The way Marclay and his team stitched together longer clips to move the hands, so to speak, kept intriguing me. A fantastic clip of Charles Bronson in flared trousers, for example, is allowed to run for a bit before he checks his pulse against his wristwatch. At other points, Peter Faulk (who appears again and again) comes and goes. There is a bit of a game in the film as you wonder what scene will click into place. But on a deeper level, there lies a rather deconstructed question of narrative—as if each of the pieces no longer has storylines of their own and instead works only as markers of the passing of minutes.

A certain dread shadows the film, both in the sense that the genres most often included were dark—thrillers rely on the clock for suspense way more than comedies—and, of course, the slipping away of your own time as each minute elapsing is showcased. On one level, it is the arthouse equivalent of one of those horrifying calendars that feature 100 years of weeks as empty blocks, and you are to tick them off as each new Sunday rolls into view. Nerve-wracking.

Made with pre-iPhone source material, The Clock also is casually dismissive of every generation’s admonishment that we are currently too time-dependent since it’s clear the evolution of film hinges on time and timekeeping, whether it’s Harold Lloyd in 1923 or Christopher Lloyd in 1985.[2] Time exists mainly in analog here, and I think I noticed only a couple of digital clocks (one, a microwave; another, a clock radio) in my viewings. More obviously, so much of The Clock exists in the world of trains, various modes of transportation, and the public space of the clock tower. These liminal spaces intersected by furtive glances, severe clocks, worried grimaces, and the noir shadows of the everyday. It is an intoxicating film.

Walking out, I asked a staff member if he had seen the entire film. He replied he had only (only!) seen eighteen or so hours overall. He said he had a love-hate relationship with the whole thing, but overall, he thought it was all necessary: a wildly experiential moment.

What has stuck with me most, however, is the literal craft of the film. Is there an actual beginning, or is it some digital loop? How was it physically constructed, sure, but also how is it screened? Are there various drafts? And on and on. The physicality and archive of The Clock loom more in my brain now than the purported subject.

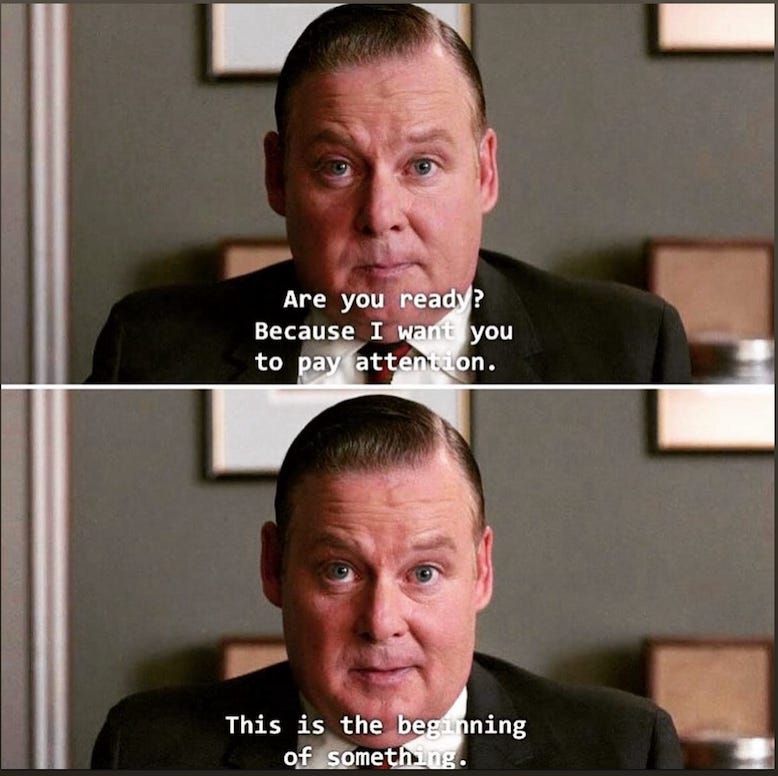

I saw The Clock on January 2nd as the New Year memes drifted past. One that always shows up on my feed is a scene from the Season Seven premiere of Mad Men (titled “Time Zones,” naturally), which starts with the sudden reappearance of Freddy Rumsen (last seen a few seasons earlier) staring directly out at the viewer and intoning:

“Are you ready? Because I want you to pay attention. This is the beginning of something.”

He is pitching an ad for Accutron wristwatches, but the framing works as a nod to the beginning of the show’s end and a setup for Don Draper’s return (as we soon discover that he is feeding Freddy the lines). The ticking clock thus serves as the backdrop to Draper trying to figure out a path forward (“Do the work, Don”).

Early last year, someone pointedly asked me if what I did was even history, which, at the time, I took as a dig at the work I was doing with Woody Guthrie, Bob Dylan, and the rest. As a cultural historian, I have often received criticism about topics I wrote and taught, but this comment rattled me, though not perhaps in the ways intended. What I now presume was just one more note of dismissiveness added to the pile now serves as a notch on whatever yardstick delineates my career. I am proud of my work generally and of the Forrest book (a book incidentally that I was finalizing the page proofs when the question was proposed), which is as deeply researched and sourced as anything I will probably ever write. Throughout the year, with time, I came to see “Do you even write history” (derogatory) as something more interesting and curious--replacing the dismissiveness with a sense of actually, I don’t know. Perhaps, then: “Do you even write history?” (celebratory).

In the classroom, the easiest definition of history for students is often the study of “change over time.” That’s it. It kind of sums up the whole deal. Pithy, though the statement obliterates the complex timelines embedded within. But telling students on the first (or last) day of class that we haven’t broached the cosmic riddle of linear time seems harsh when most of them just want to know if it will be on the midterm. And yet, we make sure our watch is in time with the rhythms of some larger, more established keeper of time. In the afternoon section of The Clock, in particular, so many actors are seen checking their watches against the authoritative voice of some larger timepiece. We judge the discrepancies on our end while ignoring the incongruities created by the city clock. All in an attempt to find our coordinates—to plot ourselves upon some unknowable graph. As the spaces between the perception of Now and whatever agreed upon authentic Now spin out in infinite circles of almost’s and not quite’s, asking, “Do you even write history?” seems like the smallest question in the world.

Bill Callahan, as always, understands:

And I set my watch

Against the city clock

It was way off

Happy New Year.

[1]Zadie Smith, “Killing Orson Welles at Midnight,” New York Review of Books, April 28, 2011.

[2]“In ‘The Clock’ there are a few flip phones, but that’s about it,” Marclay said. “It was really pre-iPhone madness. But when we started showing it, people were comparing it to their phone, introducing that element of real time in the cinema.” Marc Tracy, “‘The Clock’ Revisits New York. Is It Still of Our Time?” The New York Times, November 15, 2024.

Enjoyed this very much. I was in NYC in November and visited MoMA, but I was in a hurry and didn't take the time to visit the Marclay exhibit. So bummed I didn't. I'll be back there in June, and I hope the exhibit is still there. I wondered about the beginning and the end and how it all fuses together, which I guess is the point! Also, if someone can't see the significance of studying Woody and Bob, I don't really know what to say...

Love this essay, Court, and the non-linear, associative way your mind works. Don't know if it's history you're writing, but whatever it is, I'll keep reading it. Your piece made me think of Douglas Gordon's 24 Hour Psycho, which I never saw, but which is tattooed in my mind from Don DeLillo's detailed descriptions in Point Omega. Worth checking out.